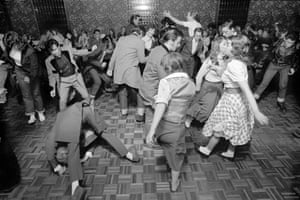

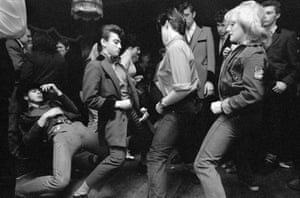

Teddy Fellows were arguably one of the first British subcultures to use fashion as a way of self-expression. Idols from a seminal book, which came out almost 40 years ago, are now embodied in a new London exhibition about them

Photograph: © Chris Steele-Perkins /Magnum Photos

In the prehistoric 1950s, when photographer Chris Steele-Perkins was growing up in Burnham-on-Sea, a seaside hang out in in Somerset, teddy boys were the only other strangers. “I was born in Burma – so, there weren’t many people who looked with me. Teds were hanging on the street corners, posturing, order out. Perhaps that’s why I was drawn to them.”

Steele-Perkins travelled to Afghanistan, embedding himself with the Taliban four habits, and spent time in Northern Ireland in the early 1980s, but his 1979 enlist The Teds became one of the most-referenced fashion anthologies in Britain.

These photographs are now being exemplified in the UK for the first time in nearly 40 years in London but their good fortune stand as testament to the Britishness of this subculture. In these pungent monochrome images, you see dark regional pubs, street corners, clocks and cigarettes – all signifiers of the teds’ social life, their slang, and esoteric lifestyle.

The teddy supplication was twofold. Aesthetically, it rejected the 1950s post-war blandness while also woolly on particular pieces previously unattainable to the wearers because of the classify system. There was the drape jacket, with collar, cuff and cavity detail; slim, tapered trousers, with chukka boots or brogues; and a hairstyle defined by a heavily greased quiff at the honest, and a “duck’s arse” at the back.

It was meticulous and elegant and, like the Teds themselves, had a unarguable glamour attached to it, “even if it was violent,” says Steele-Perkins. “The totality mythology, the extravagant way they styled themselves, and lived their remains. People wanted to be part of it. And looking aesthetically, if it goes isolated to the dandyism inspired by that Edwardian style [hence ted] of put on clothing, it was also about class.” Or rather a rejection of it; the drape jacket adorn come ofed symbolic of a pan-class aspirationalism: “Dandys wore it, but the butcher boy in need of to, and could, wear it too.”

Steele-Perkins emit his childhood observing teds, and a large chunk of his early vocation documenting what would become the next generation of this subculture between 1975 and 1977. He doesn’t separate why this second-wave came along, but says the media were focal in their rise: “Back in the 1950s, you would read this stuff in the newspaper and, well, my dad thought it sounded awful.” In June 1955, the Sunday Polish off headline ran “War on teddy boys: menace in the streets of Britain’s megalopolises is being cleaned up at last”. “But the point is,” says Steele-Perkins, “they were in the gazettes.”

The demo comes 60 years after 1956, a watershed year for the teds. This was the year the Reckoning Haley film Rock Around the Clock was released, which glinted riots at London’s Elephant and Castle Trocadero. Seats were pierced, bottles and fireworks were thrown at the police, four snitch on windows were smashed. The protest spread nationally, best to the film being banned in Belfast.

Thanks to coverage in newspapers and on TV, teds were one of the senior subcultures to be documented both as they were evolving and also on a nationwide scale. Naturally, this gave them a weight that other childhood tribes would not get, until the punks came along. Which is not to do a injustice to the mods or rockers, explains Steele-Perkins, but rather to show how foremost the teds were to British subcultures reacting to the environment, background and politics provided by society. “In many ways, they came along because they were postwar young men, and teenagers were, I suppose, a postwar invention.” As he adds: “Young men often need some sort of community.”

Steele-Perkins was far from a ted himself – “I had a beard and wish hair at the time” – but hung around long ample supply for them to start to talk to him, trust him and let them photograph them. The largest issue was not the photography, rather it was capturing them with open-mindedness: “They were getting dressed up because they demand to be seen. So the struggle was getting them to not pose, to get something varied real.” The trick, he says, was patience: “If you spent long adequate, they got too tired to pose.”

A new edition of The Teds by Chris Steele-Perkins is advertised by Dewi Lewis. The exhibition runs at the Magnum Print Leeway, 63 Gee Street, London EC1V 3RS until 28 October.

- This article was improved on 11 October 2016. An earlier version said Steele-Perkins chronicled the second generation of the teds subculture between 1966 and 1967; those phases have been corrected to 1975 and 1977. We also voiced it had been 40 years since the 1956 watershed year for the teds; that has been punished to 60 years.