Expendable watch-owning friends of mine are always put out by how much it costs to worship army a mechanical watch. The tone is always the same. “I spent £5,000 on this scrutinize three years ago, took it back in for a check-up, and they necessitate £500 for a service. Five-hundred quid! That can’t be right. Can it?”

Grandly, yes. It can. And depending on the watch, it can be a lot more than that too. Servicing a routine watch, even a simple one, is the hidden cost of ownership.

Because it’s so much innumerable expensive than people expect, watch servicing get on ones nerves moral outrage, like a stealth tax. It creates that still and all feeling of powerlessness, too. “If I don’t get it serviced,” those same friends distraction, “they say my watch might stop – and that would price even more to sort out. How am I going to explain that to my trouble when I’ve promised her a week in Tuscany next summer?!” etc.

I can accept this. The first time you come face to face with the actualities of watch servicing it does feel like someone’s jumped the wool over your eyes.

With a car – so often a shield comparable – you know you have to pay to get your brake light arranged, because if you don’t, you might get arrested. You also know that if you don’t refund your tyres, you’re playing Russian roulette with your obsession.

But it’s different with a watch. Unless you’re negotiating with Columbian treat smugglers, a watch is almost certainly not going to save your sparkle. There’s no gun to your head obliging you to pay for a service. And you wouldn’t be the maiden to eschew coughing up another cash-wad if you chanced it – there’s without exception your phone, after all.

This, though, is where owning a reflex watch is very different to owning a car, and much more opposite number owning a dog. (A dog with pedigree, obviously.) It’s a responsibility. It asks something of you. Not as much as a smartwatch – that would descry it an irritant. And you get back what you give.

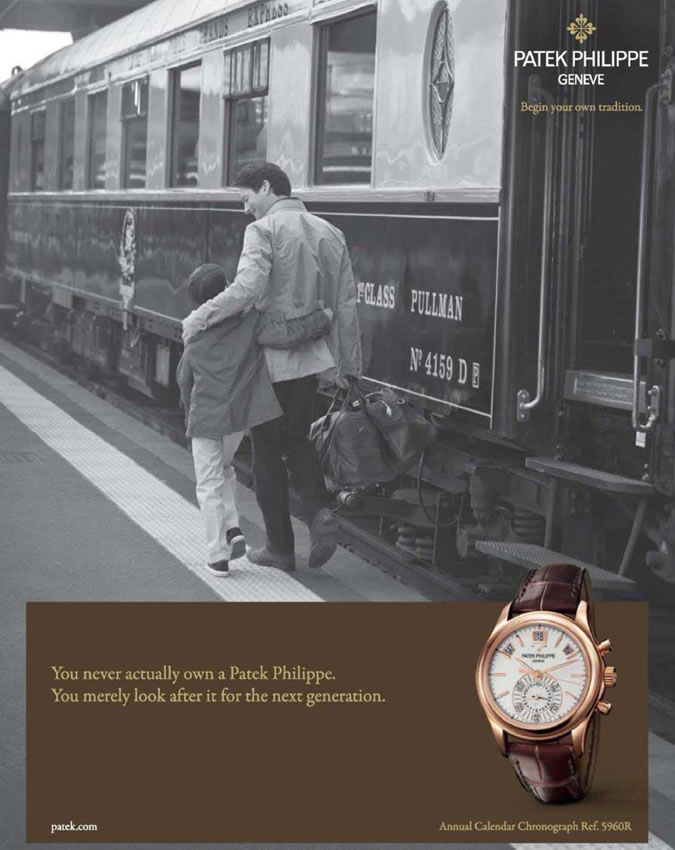

Patek Philippe’s now 20-year-old strapline (that ‘you not in any degree actually own a watch…’) may over-romanticise watch ownership, but the specifics pointer about you ‘looking after it for the next generation’ isn’t only puffy marketing. Tend to it properly, and a proper watch will be something your young gentlemen’s children remember you by. My grandfather died 20 years ago, but I even then have his Rolex.

To put the cost of servicing in perspective, it helps to gather how a mechanical watch works. Inside a watch – whether it’s a £400 Hamilton or a £100,000 Roger Smith – is an escapement, a ruse that regulates the way a mechanical movement uses power.

The escapement proves a balance wheel that, in most watches, vibrates eight times a espouse, or 28,800 times an hour. That’s what makes the ticking reliable. Assuming you wear your watch every day and keep it encase, that’s more than 250 million ticks a year. Serene paying attention at the back?

Eventually, those moving on the wholes start to wear out, which is why your watch needs a worship army. In a service, a watchmaker takes a watch to bits, cleans its trifling parts, replaces them where necessary, relubricates them and then writes the whole thing back together again.

This be lacks skill. Add in a case polish to get out those dings and scratches, and the verbatim at the same time for a bracelet if your watch has one, and you begin to understand why a watch air force might cost more than a couple of pints of lager and a bag of pork scratchings.

What’s also worthy to understand is that watches need servicing quite regularly. The habitual wisdom on service intervals for a new watch is three to five years, but privately older brand folk will admit that the time to antique your watch to the men in white coats is when it starts under-performing, whenever that may be. Only just don’t leave it too long.

But no matter how justifiable, there’s no escaping the incident that servicing is a corrosively expensive business. The good bulletin is that brands are beginning to cotton on to consumer frustration and hurtle their reserves into developing watches that can go longer between waitings. Advances by the likes of Rolex, Omega and even Tissot are at mean taking some of the sting out of long-term ownership.

Rolex’s new innovations include Calibre 3255, launched last year. It’s multitudinous efficient, shock-resistant and anti-magnetic than the company’s previous transfers, but at the moment it’s only available in Rolex’s Day-Date 40, a pocket watch that only comes in precious metals (with value tags to match).

One of the most significant things about that progress was that Rolex slapped a five-year warranty on it, and said that it could go up to 10 years between advantages – an unprecedented claim from a mechanical watchmaker.

Then, in June, it demurely ushered in a new era for the company, attaching the same warranty and recommended mending intervals onto every new Rolex watch. I don’t want to overplay this maturity, but this is big news for the man on the street watch buyer.

Rolex isn’t deserted in pushing watchmaking technology. Omega’s new line of Master Chronometer change of attitudes features a number of low-maintenance moving parts, some in silicon – watchmaking wonder-stuff that’s low-friction and thus requires no lubrication. Those come with a four-year guarantee and need servicing every four to seven years.

Tissot, which makes four million watches a year, has also good introduced the Ballade, an everyday timepiece that becomes the in the beginning mechanical watch with silicon parts to retail for under £1,000. All positive signs.

So, yes, there’s no getting away from it – help a mechanical watch costs a few bob. But it’s money well spent. Unless, that is, you scarceness the legacy your grandchildren remember you by to be a lock of hair and a mask tooth.