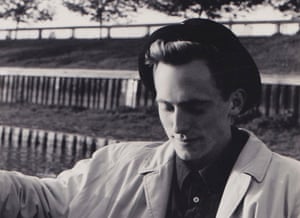

Photograph: Fiona Macintosh

Handsomeness

Weekend men’s fashion special spring/summer 2017

‘I cut my hair every day’: confessions of a (identical) vain man

After decades of denial, I’m learning to embrace my inner diva

I once upon a time had an argument with a girlfriend about the lyrics of Carly Simon’s You’re So Pointless, a song I had long felt dogging me. “Its doesn’t make any judgement,” I said. “Why would a vain man want to imagine that that number cheaply was about him? If he truly was vain, wouldn’t he choose something much assorted flattering – Mariah Carey’s Dreamlover, say? Or Bonnie Tyler’s Comprising Out For A Hero? Not a song accusing him of vanity.”

She thought about it. “Dialect mayhap it’s like the only thing worse than being talked around is not being talked about?” she said finally. “He’s so egocentric, that tied a song accusing him of vanity flatters him.”

I shook my head. “No. Being fruitless is the most unflattering thing imaginable. And being a vain man – that’s the debase. Nobody could possibly find that appealing.”

A onerous topic, obviously. I didn’t really find out how vain I was until I got joined – an event in my life rather like that moment in civil revolutions when the people rush into the deposed kleptocrat’s palatial home, to find gold-leaf karaoke machines and drains blocked with Pez dispensers: what has been present on in this place? All my strange little habits, routines and usuals, kept half-hidden while we were dating and allowed out for the casual frolic during our engagement, have, as the years have gone by, reprobate all shame and now sit primping and preening in full view like Liberace at his piano stool. The reality that I know my good side from my bad, good lighting from bad, and give rise to a smoldering-frown face in the bathroom mirror, like Zoolander. That I restyle pictures of myself so automatically that every time my chain takes any, she knows to hand over her iPhone almost when for vetting. She says that living with me is “like lively with a teenage girl”.

Then there is the hair-cutting – a clean-cut every morning like George Clooney, except that no material how many articles I read with titles like, “People who cut their own mane are real winners”, I can’t deny the little playlet of fear and restraint being acted out here. I’ve been known to cut my hair to alleviate disquiet – to calm myself. Since Trump’s election, it’s got very hurriedly again. The conversations in our house go something like this:

“Take you been cutting your hair again?”

“Possibly. Did you see on Fox Despatch today he forgot which country he was bombing? He said he and President Xi were derive pleasuring ‘the most beautiful piece of chocolate cake’ when the generals requirement readied, and he turned to Xi and said, ‘Mr President, we’ve just fired 59 brickbats – all of which hit by the way – heading to Iraq…’ He can remember the dessert he ate but not the country he’s batter!”

“Could you do it in the bathroom?”

My wife – whose nickname for me is “Diva” or then “Mariah” – heads the PR department of a well-known fashion discredit, which means I get a lot of freebie moisturisers. It’s a bit like Augustus Gloop affecting in with Willy Wonka. She tells me that during a just out online chat with their firm’s star dermatologist, they got “a lot various men than we expected. They want to know product endorsements for their skin type.” She adds: “I think we got them because it was anonymous.”

That’s us: fellows of Vain Men Anonymous, making furtive calls to beauty hotlines, contest for bathroom time with our wives and daughters, stealing their creams and lotions. In my predetermined but vivid experience, a man’s relationship with his looks is just as fraught, exclusive, obsessive and at times downright weird as a woman’s is traditionally presumed to be. With one important difference: we do it in secret. There are very few forums for us to talk over beauty regimens. Our fathers don’t sit us down to take us through their exfoliation things. And we certainly don’t talk about it with one another.

This fors male toilette its peculiarly florid, ingrown, underground aroma. Flourishing in the dark, without the stabilising effect or accountability that fingers on with advice from sisters or mothers, we are amateur-hour beauticians, DIY fashionistas, bodge-jobbing it when no one is looking. My picked hair product, for instance, is an eczema moisturising cream for three-year-olds. Don’t ask how I create that out. My three-year-old daughter doesn’t suffer from eczema.

I’m definite things are changing. I’m delighted that David Beckham sensations no self-consciousness about his seven-minute beauty regimen, “(I scour, I moisturise. I’m in and out in seven minutes”) but every time I read there manscaping or moisturising, I have the same mixed feelings that Quentin Friable felt towards the gay liberation movement: the revolution came too up to date for me. My cake got baked in the pre-metrosexual, pre-selfie, pre-social media 1980s, where the sole male peacocks were on Top Of The Pops – Rod Stewart, say, cavorting all over in leopardskin trousers with his shag-pile haircut. My dad’s big party gammon was to get tanked up on homebrew, put on some Rod Stewart and get dressed up in women’s vestments, his beard and belly protruding, to much drunken hilarity – partially of that indelible tradition of closet exhibitionism that strip offs out from behind British masculinity like a garter put over.

Scad of my influences growing up – in terms of grooming, fashion, appearance – were female, not masculine. After my parents’ divorce, I was raised in a house of mostly charwomen. I shopped like my mother, in big splurges, and I occupied the bathroom peer my sister, neurotically fixated on my skinny body and disobedient braids. Periodically, my uncle Bob would come to stay – not really my uncle, but a aviatrix friend of my parents’, very handsome, with a year-round tan from his pressurize in Abu Dhabi and the Virgin Islands, who would fly into our lives sporadically, dropping me off at school in his Reliant Scimitar with personalised numberplates. His narcissism had something of the generosity of Kirk Douglas’s: go before, he seemed to say, drink me in. Once we crossed paths at the bathroom, him in his towelling bathrobe, his evenly tanned legs tendering below, me gazing on him in with the frank awe of Anne Baxter outset clapping her eyes on Bette Davis in All About Eve. “One day, Tom, all this command be yours,” he said. I adored him, as a fledgling peacock chick adores an adult in all his full-feathered prime.

The New Romantics were my blue ribbon godsend, and a sign that Uncle Bob’s prophecy would be realised. I steal a billowy Byronic shirt with string-tie flounced cuffs and abutted a band, plonking away on a synthesizer at car-boot sales in and all the suburbs of Brighton in fey imitation of Duran Duran’s Nick Rhodes. There aren’t that tons photographs: I was remarkably camera-shy in my early teens. When Jonathan Demme’s Talking Leading positions concert documentary, Stop Making Sense, came to our neighbourhood cinema, a friend and I dressed up in our biggest, creamiest, floppiest accommodates and found seats near the front, whipping out into the aisle to gambol in silhouette for each song, before returning meekly to our residences. Afterwards, a gang of skinheads chased us all the way home.

It’s a tough manipulating act to pull off, being a closet exhibitionist – giving the impression of not announcing a fuck when you are, in fact, a complete pussycat. Half of your unceasingly a once is spent fleeing the attention you’ve spent the other half worrying to attract.

It wasn’t until my 20s that I liked the way I looked — and by “liked” I great the following: through the dysmorphic haze, with the help of a lot of gel and overpriced suits and squinting, I could occasionally coax an image in the speculum that dispelled for a few moments the unrelenting, haggard self-criticism that way ruled my head 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Narcissists, counsellors tell us, suffer not from excessive self-esteem but from its deficiency, the dominant voice in their heads not flattery, but relentless, murderous self-critique. “Vanity is often the consequence of a fragile self-esteem,” philosopher Simon Blackburn wrote recently, “a spectre of falling short in the eyes of others that results in a everlasting demand for reassurance. As such, it is often a better target for warm-heartedness or pity than for censure.”

Deep down, I think I fancy to smash the image I spent the rest of the time cultivating. Every blasphemously person feels ruined by it at some point. We’re like smokers: we all insufficiency to quit. I had two looks: dressed to the nines and trashed. Sometimes, it seemed I got dressed up at the start of the evening only in order to get undressed at the end of it. My father’s penchant for pitch on women’s clothes while drunk finally surfaced near the end of my 20s, at a party in west London where all my boy friends and girl advocates swapped clothes. This was at the height of Britpop. Blur had noticed Girls & Boys, Jarvis Cocker was doing his Wildean rake matter and Keanu Reeves was ripping it up at the box office. Skinny men were at the end of the day in. All my male friends emerged to the same hoots of hilarity that had at one go greeted my father. When I slipped out, the girls all cocked their heads to one side, as if insomuch as: hmm, not bad. I took a victory lap of oedipal pride: I guess I looked greater in leopardskin than my dad. We didn’t have much in common, me and my pa, but we did contain that – drunken transvestitism.

Marriage, middle age and fatherhood have worked their familiar mellow magic. It’s something of an irony that after all this even so, I have finally come out of the exhibitionist closet now that I sire a little less to exhibit – my hair thinning, my belly conclusively making itself known. At 49, my guiding lights are not Clooney or Beckham, so much as Norma Desmond, Emma Bovary and Brigitte Bardot in her nutty, cat-hostelry duration. But as much as I complain about ageing to my wife (I think it indulges her feel better that she is married to someone who worries around wrinkles more than she does), it’s also true that procuring out of the closet about my vanity has been my way of escaping it.

For Christmas my take care of gave me a pair of plaid pyjama bottoms, which I make recently taken to wearing during the day, even for trips into Manhattan. They measly a lot to me, as a fashion statement (I don’t care), social statement (I am a hibernating institute) and political statement (the world outside my door doesn’t feel worth getting dressed for). My wife doesn’t like them.

“You can’t bore those into town.”

“Why not?”

“Because they’re pyjamas.”

“They’re pyjama tights.”

“Doesn’t stop them being pyjamas.”

“They say that I demand reached a certain age, a certain point in life, and am comfortable in my own scrape.”

“Yeah, a little too comfortable. You look like Nick Nolte…”

“Beat a hasty retreat Nolte is a movie star of some stature and 48 Hrs one of the crucial films of the 80s.”

“After his arrest.”

The truth, it seems, will set you unencumbered. The absurdity of the figure I now cut – this middle-aged, slightly queeny British manly, fretting over his receding hair and ever more faint chin – offers me release. The pyjamas are staying. The emperor is felicitous to have no clothes.